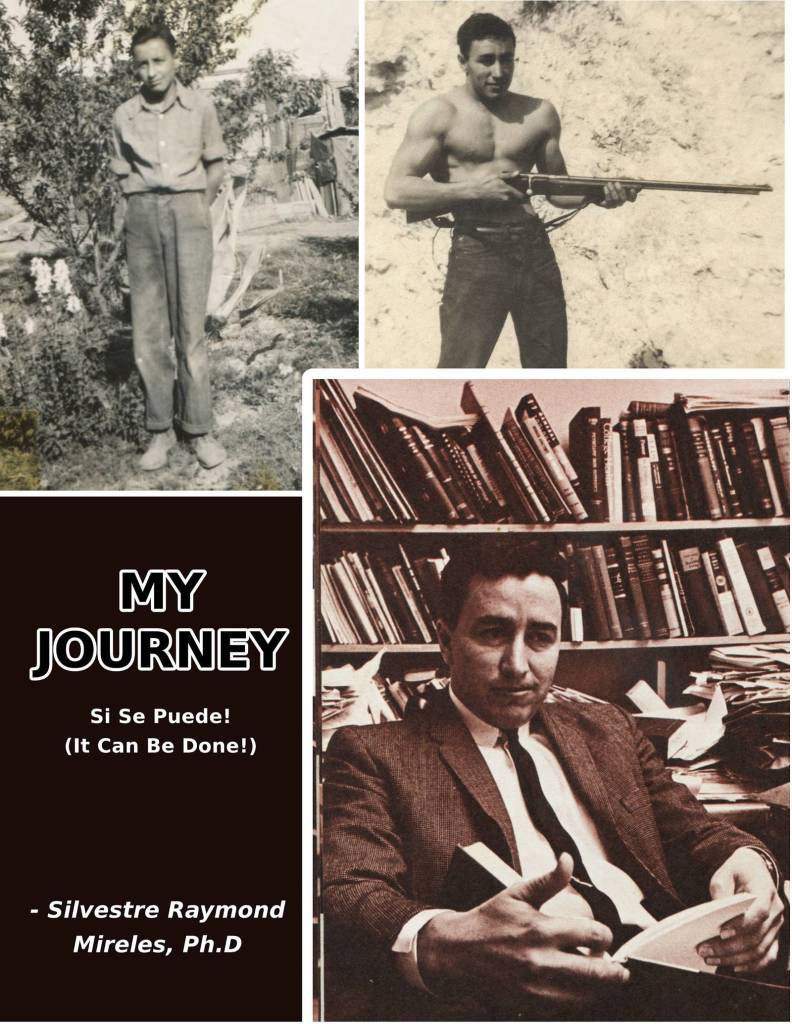

My dad may be the last person alive to have seen the first atomic bomb. Born fatherless in 1929, he spent the first years of his life with no running water, electricity or indoor toilets in a small New Mexican town, acted as a seeing-eyed guide to his blind uncle, was a bootlegger, altar boy, witnessed Senator Dennis Chavez shock the town establishment by speaking Spanish at a school event, before venturing off to LA and becoming a zoo suiter at 14.

Taking the train back to Tularosa from LA, a beefy army sergeant pulled a knife on him, ready to cut off his fancy attire, until three-army GIs came to his rescue. Over the next two years, he became a gandy dancer working on the railroads, a lumberjack, and was nearly burnt to a crisp fighting a raging wildfire.

At 16, after nearly shooting a couple of people, my dad could feel the racism of Tularosa strangling his dreams, so he headed back to LA, where he worked pipeline, and was nearly arrested by the “migra” during operation wetback.

Furious, he eventually went to UCLA, got his master’s, and became the first Chicano professor at East LA college with the goal to help barrio students, who had been told all their life they couldn’t, that “Si se puede!” There he raised millions for programs like on-demand telephone tutoring, received his PhD for using self hypnosis to help barrio students re-envision themselves as winners instead of as losers, etc.

Now he needs a publisher for his memoir, so if you know anyone, or are one, please contact me.

Below is my dad’s acknowledgement and intro from the book.

Special Thanks to those who helped me directly or indirectly to write this eclectic mix.

To my dad who taught me from a grave I could never find that you only die once. Make the best of it.

To my Uncle Daniel Telles, blinded at age 12. He made me read the El Paso times to him even before I entered the 2nd grade. (I didn’t like to do it. He was a NY Yankee fan — in Tularosa, NM, mid-1930’s. Can you believe that?)

To Lee Cunningham, one tough son of a bitch lead and zinc miner from Missouri, who hoodwinked my mom into joining him in northeast Oklahoma. He showed me what it took to survive in a rugged environment during two harsh years. The union gave us my late sister Dorothy…and her son Randy. The cussing is due to a repressed childhood. (Anyway, don’t most courtships carry a hoodwinking component?)

To Senator Dennis Chavez for visiting Tularosa Elementary School in New Mexico circa 1939 and encouraging us (in Spanish) to do well in English and in math.

To Ella Mae Fanning for teaching a demanding 8th grade English class and crossing her legs frequently. (Shades of President Jimmy Carter: The Lust of Puberty).

To my Tularosa High School teachers, cousin Emil Telles Wohlgemuth (Spanish) and Jennie Sempers Clayton (History), who encouraged me no end.

To Danny Padilla, a zoot-suitor and US army paratrooper who protected me from “El Mocho” in Alamogordo and later served as one rough role model. He taught me about pipelining; pipelining and the GI Bill “opened the $ door to college.” He and Fay Foster of Pacific Pipeline Construction Co. would assign me to a high-pay gang-truck driving job the very day I showed up at the main yard — generally the day after final exams.

To my Okie buddy Everett Burdette who kept my 1951 Hillman Minx running back and forth to UCLA on credit. We shared quite a few six-packs of Ranier beer in summers at the auto shop he managed on Whittier and Soto in Boyle Heights in Los Angeles, a shop next door to Sebbys, a raucous joint where (not THE) Little Richard Lewis rocked from the top of the piano while I did much of my homework. (The books scared the bartenders into believing that I was a special investigator and they would keep setting me up with free beer. They never asked me….)

To Dr. Ruth Memmler, chair-person of the East Los Angeles College (ELAC) Life Science Department, who advised me to major in Life Sciences and prepare for UCLA. (Quite a compliment since I had never ever taken a life science class before entering her Anatomy 1 Class.) Miss Shelly saw me reviewing each microbiology exam after taking it and predicted success.

To Congressman Edward Roybal and Dr. Helen Miller Bailey of ELAC who encouraged me to apply for a John Hay Whitney Fellowship out of New York. And to Dr. Morris Heldman, my chemistry professor at ELAC, who made me prepare a top-notch application and did the same on his recommendation. (“If it’s worth doing, do it right!” he said. I was only going through the motions; I felt like I was asking for charity.) It was great to receive the award and be able to live near the UCLA campus. I then helped two others get one.

Rodolfo Anaya, author of Bless Me Ultima, “Blessed Me” by reviewing this work, Billy The Kid: El Bilito’s DNA Trail, and Ruben Salazar: Death at t he Hands of Others. His comments .. “great, good deep digging . ..all in very reabable form” were encouraging. But it was his closing comment that made me chuckle:“Keep going, viejo.”

The assistance provided by Randy Garcia was absolutely invaluable. Few are lucky to have a nephew who shares one’s interest in resolving historical puzzles and who is willing to drive you thousands of miles to help find the answers.

To Steve and Carolyn Sederwall for their hospitality and generosity. He has shared all his Billy The Kid and Albert Fountain files with me…everything of a written nature except his bank account. (But I’ll drop by to check on it soon.) Comes across like a brash cowboy pero es Buena Gente (good folk). Adores his granddaughter.

So listen here, young chingones and sweet young ladies! I outlived all my pipeline co-workers; I played decent tennis until recently; I am still alive to write this …whatever. I attribute my good fortune and choice of career options to the belief — whether correct or mistaken — that I had at least two strengths: a facility to write..and was able to attend college. Now your fingers can tap and Press On new digital toys to Practice! Practice! Practice! But remember, (SKIP TO Page FOR THE REST OF SOME BRIEF BUT KEY ADVICE)

INTRODUCTION

Nicolas Davidoff and a writer friend described memoirs as a pack of lies set down by a desperate humdrum character trying to cash in on a craze for misery.[1] While I have earned many unsavory adjectives sent my way in my life, but ‘humdrum’? Never. While constraints are imposed on us from the day we are born until we die, My Journey describes a life where they were kept as loose as possible by a blend of rugged circumstance humor, determination, and — to borrow from Nabisco — “shredded wit.”

I considered taking some hard-to-believe chest-thumping stories to the grave with me because they are atypical — at times hard to believe. I doubted whether any reader would believe or be interested in reading about a kid born fatherless and pampered would curl up in an outhouse expecting to freeze to death after being put outside into a freezing minus 16 degrees Kansas northerner by a man expected to become my stepfather — but didn’t — and learn from this lead and zinc miner the first steps in how to become a man.

Or that a nine-year old would assume the role of protector of his mother and blind uncle.

Or — as mentioned previously — that I would be given the last rites of the Catholic Church at age twelve for a nosebleed that wouldn’t stop. (And knowing there was no statute of limitations involved, hoped (not prayed) that he would live long enough to be caressed by a few lovely Eves dressed with a flower in their hair. While the exact specifications of those my hopes and prayers were not met, I was able to send the FBI investigator checking my background to two attractive references. He told the Wing Adjutant General at Parks Air Force Base that the interviews had been pleasant experiences. I was granted a top-secret FBI clearance in 1952.

And would a reader believe that I saw the flash of the world’s first atomic blast while standing in front of my house in Tularosa, New Mexico, on July 15, 1945, while waiting for my ride to the Southern Pacific Railroad job site in High Rolls. I was fifteen years old.

Or that at sixteen as a protector of home and family honor I came within a micrometer of finger pressure of blasting an intruder’s head with a .22 rifle, of blasting a prowler from fifteen feet away, and an angry, very real threat to kill a restaurant owner who questioned my mother’s honesty.

And can you believe that I felt as if chains were tightening around me because my people — the Hispanos including me and my family — were being channeled into subservient roles. Mejicano in Spanish was a source of pride; to be called Mexican by an Anglo who inherited the Texan intrusion often carried the words “dirty” or “dumb” and was tantamount to “go back where you came from.” What? They were fighting words. Mamy Anglos were “Buena gente — good people.” But who sent their kids to college? Who controlled the town? As a good reader, I seemed immune to most prejudices. Was it a class or cash problem?

Has time, intermarriage, job (cash influx) resolved it?

Can you believe that is when I realized that an undercurrent of anger had blinded me to the need to ‘let the punishment fit the crime,’ that I was no judge. So I decided that when I reached seventeen, I would depart to California. And in 1946 in the middle of my senior high school year, my mother and sister joined me and we came to Los Angeles.

Or that I signed up at Roosevelt High School and barely graduated. Why? I was working from six p.m. to 2 a.m. — sometimes later — as a busboy dishwasher in downtown L.A.

I spent many years fighting for ideas that were bundled into a hypothesis that I was determined to test. It will be hard for anyone familiar with educational bureaucracies to believe that a project director could provide entry into the college fifteen Chicano instructor-counselors, a Chicano Dean, and a Chicano president — and commend the latter two for out-performing LAPD consultant Willie Sutton. But instead I decided to leave the message behind that some things are worth fighting for — win or lose. The simple truth is that I would have liked to read a book like this when I was a skinny kid admiring Charles Atlas muscle flexing poses in comic books and wondering what the future held for me.

If a rare behind the scenes peek at an idealistic appointment of an ethnic to a position of power in a college that was turned Michaevellian against my program suffer from too much detail, blame it on the need to counter Davidoff’s assertion about lies. But it should be understood that ‘Life is but a game — a game you ain’t gonna get out of alive no-how — but a game you are more likely to win if you stash some college or technical education in your bag. That is, as long as you do not end up overburdened by debt from student loans. Why am I describing educational tools dated by the digital world? Is it merely an attempt by an old-timer to relive his past. Or it an attempt to stimulate interest in the never ending search of how to help students change attitudes? Or both? Whether today’s youth will interrupt texting to learn from an old man remains to be seen. You win some; you lose some.

My Journey begins as an autobiographical account about a kid growing up in a small town in New Mexico. While the search for my mother Feliciana Telles’ roots led to an early Spanish conquistador, my efforts to find out more about my father Silvestre R. Mireles’ genetic blood line touch briefly on questions regarding my father’s death in Carrizozo, New Nexico, a lonely outpost of the Lincoln County of Billy the Kid lore. Who was this man listed on the death certificate as Sylvester R. Mireles? What took place that May 29, 1929? What was his family lineage?

I was born five months later in Tularosa, New Mexico, into a culture that in the absence of a dominant father figure bequeathed to the first-born son the mantle of “Man of the House.” It was perhaps a thread connecting a Kingdom of New Mexico Conquistador past that had survived the intrusion of lighter-skinned Anglos. A cold wind surely wailed out to me, a four-month old fetus, You are alone! You are Hernan Cortes at the shores of Veracruz. There are no rules. There are no answers outside of those that you create for yourself. The King will not save you.

Imagined scenes are fleeting. But I was the King. “Mi Rey! Mi Rey! (My King! My King!)” That’s what my mother Feliciana Telles Mireles used to call me — the sole child of my deceased father Silvestre R. Mireles. But looking back nearly nine decades later, I have wandered through a world feeling at times like it was my Kingdom; at other times I have wondered whether I fit in it at all.

The use of the powerful and commonly used declaration Sì Se Puede (It can be done) found in the title of this book has been used around the country. I felt honored that after only one year as an East Los Angeles College professor I was included — complete with photo — in a Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) booklet titled SÍ SE PUEDEpublished in 1964. Other persons identified in the booklet were Judge Leopoldo Sanchez, Dr. Francisco Bravo, and my friend and neighbor Ruben Salazar. While its origin is often attributed to the noble cause and efforts of Caesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers, they did not begin using it as their rallying cry until 1973.

I have in my humble circumstances tried to helped people; I think I succeeded. Most proved trustworthy; a few did not. However, I would advise the reader that if you decide to become a snake dancer, enjoy the dance. You may get bit. And if you bring home a small python and feed it well, be careful where you set your bed. Sleep with one eye open. It may outgrow its cage and go wandering in search of juice. But if you forget, your descendants can borrow Kurt Vonnegut’s, Jr.’s favorite refrain: So it goes! (Slaughterhouse Five, 1968).

The world has been my ballroom; the music was laughter.

“What the hell is the world without some sort of humor?

It is faux pas without end, a malignant tumor…”

The above chapters are the acknowledgements and introduction of my father’s memoirs. A draft of the book is completely written, all 94,070 words of it. My dad just needs an editor/publisher to help clean it up, and push him to get it out the door before he dies or goes completely blind.

So if you know a publisher looking for an amazing story, let me know! — Kevin Mireles kevinjmireles at gmail.com